“I help companies navigate the bumpy road of scale-up, providing process development services to validate key technical concepts, optimize the right parameters, and derisk the technology. I also enjoy working with clients to build capability. Going beyond producing deliverables, I view a project as a success, if I can transfer my knowledge and learnings so that I am finally no longer needed,” says Dr. Michael Schultz, Principal at PTI Global Solutions.

Dr. Michael Schultz enjoys the challenge of solving difficult engineering problems to reduce carbon footprint and to deliver economic value. As Managing Director of PTI Global Solutions, Michael works with companies in the sustainable technology space to help accelerate commercialization, reduce risk, and get the greatest value from these great ideas.

Previously, Michael held positions at LanzaTech, Battelle Science and Technology Malaysia, and UOP, leading process R&D and scale-up across a broad range of chemical and biological technology areas. Michael holds a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Michigan and a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Massachusetts. He received the 2015 EPA Greener Synthetic Pathway award from the US EPA and the 2005 Haden Freeman Award for Engineering Excellence from IChemE. Mike has been granted more than 45 US Patents in his career.

Sign up to meet Michael Schultz on August 25 to discuss “Financial Instruments for Scale-up of Sustainable Technologies”

Contact Michael Schultz with your interest in Scale-up of Sustainable Technologies.

Sebastian Klemm: You recently presented “Practical Guidelines for Scale-up of Sustainable Technologies” at the Process Development Symposium in Philadelphia. What are the cornerstones of these guiding principles of yours?

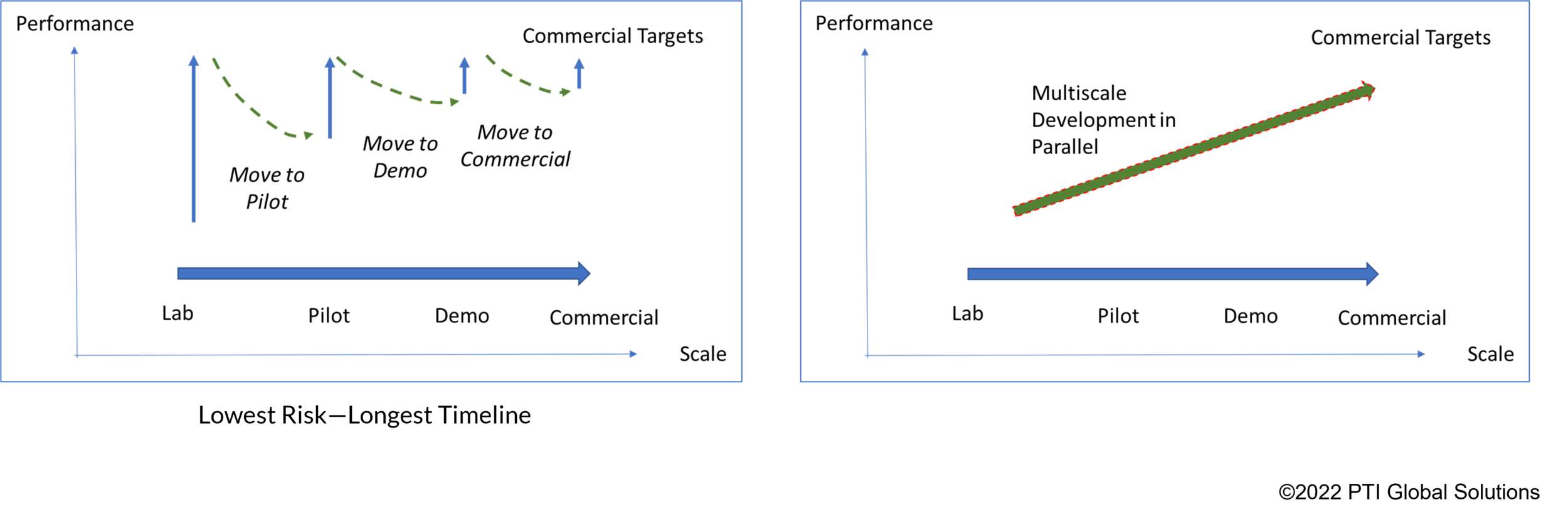

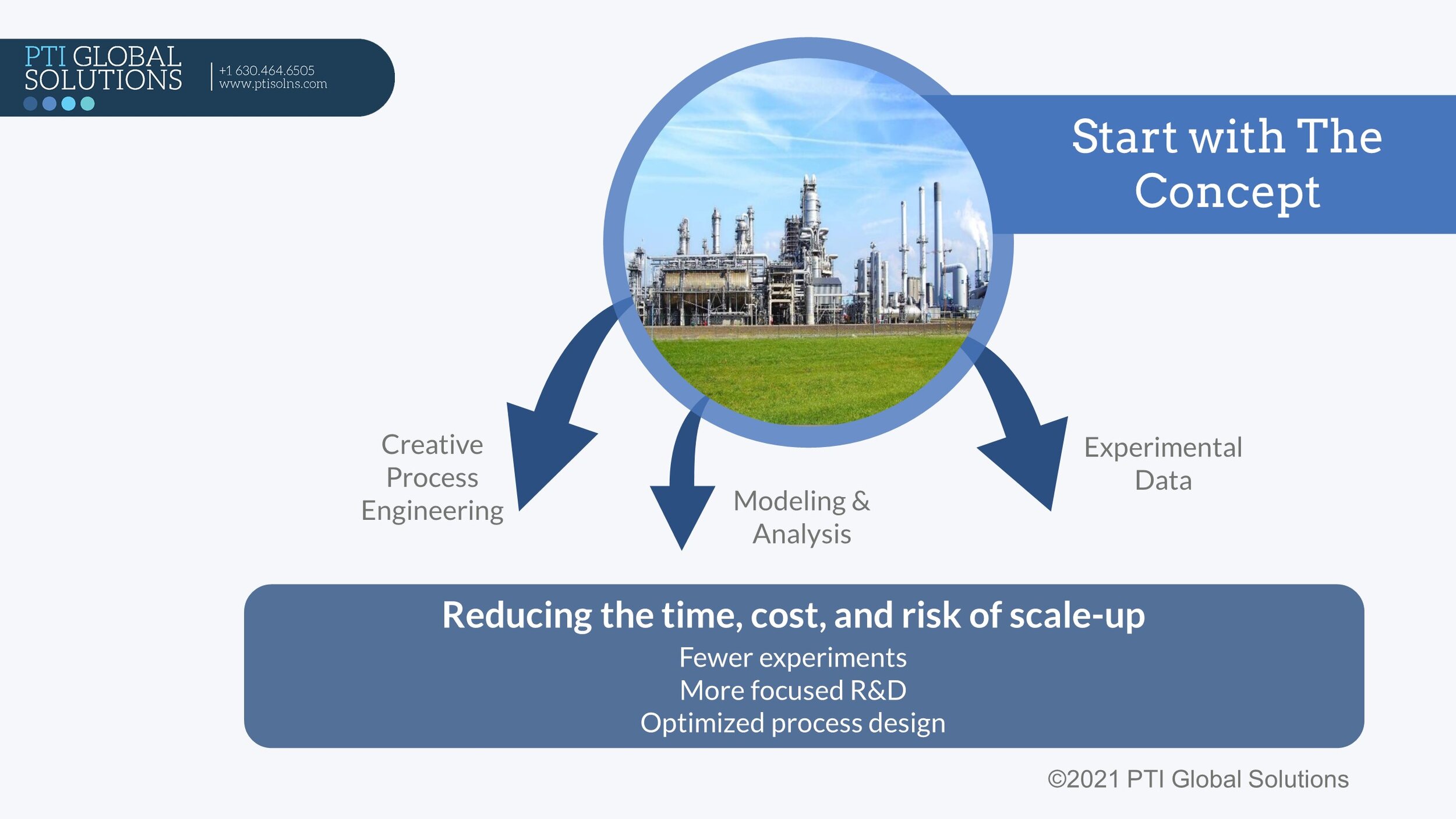

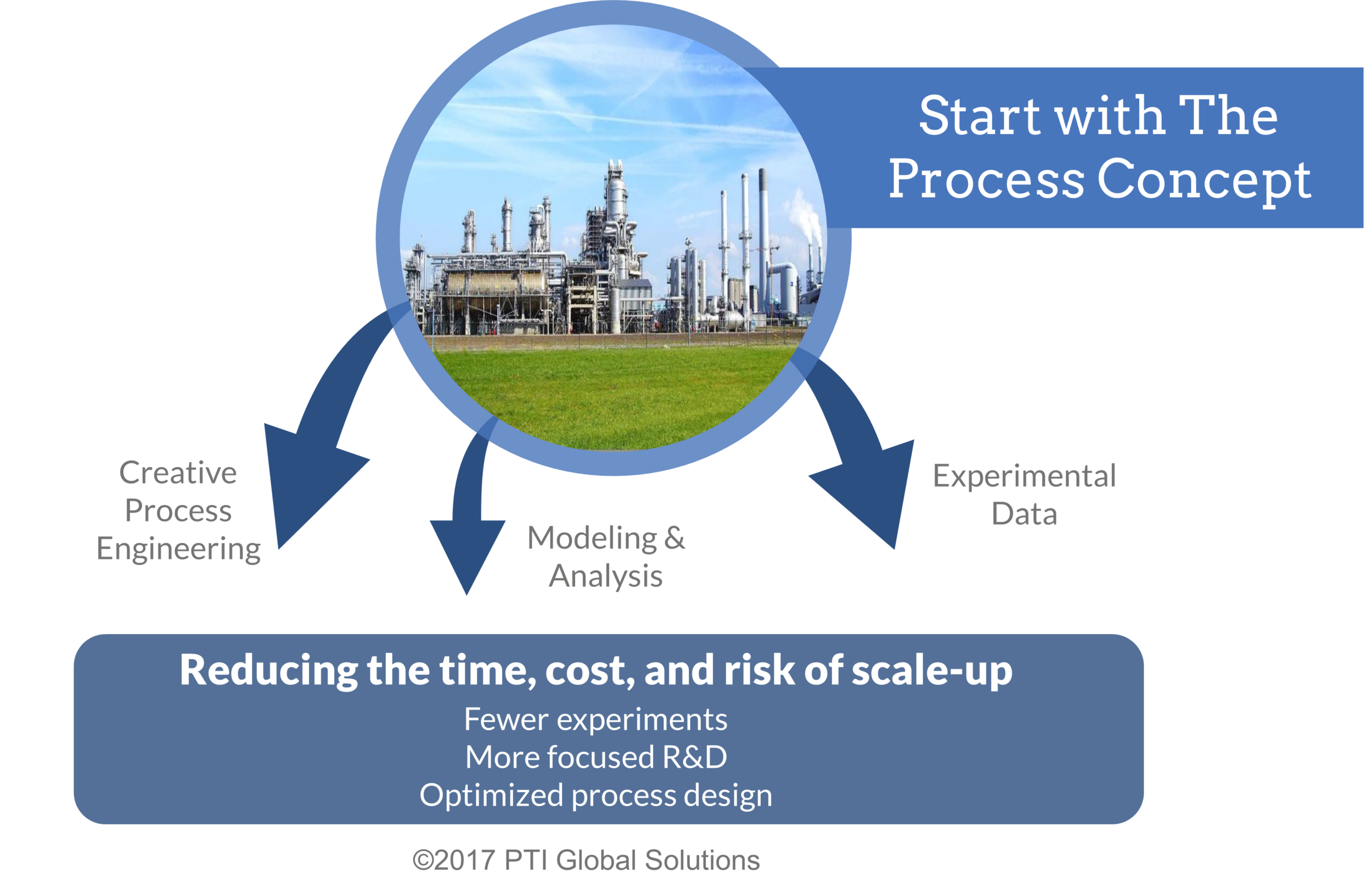

Michael Schultz: The challenges with scale-up of sustainable technology are to effectively reduce the time, cost and risk of scale-up. These are often competing objectives.

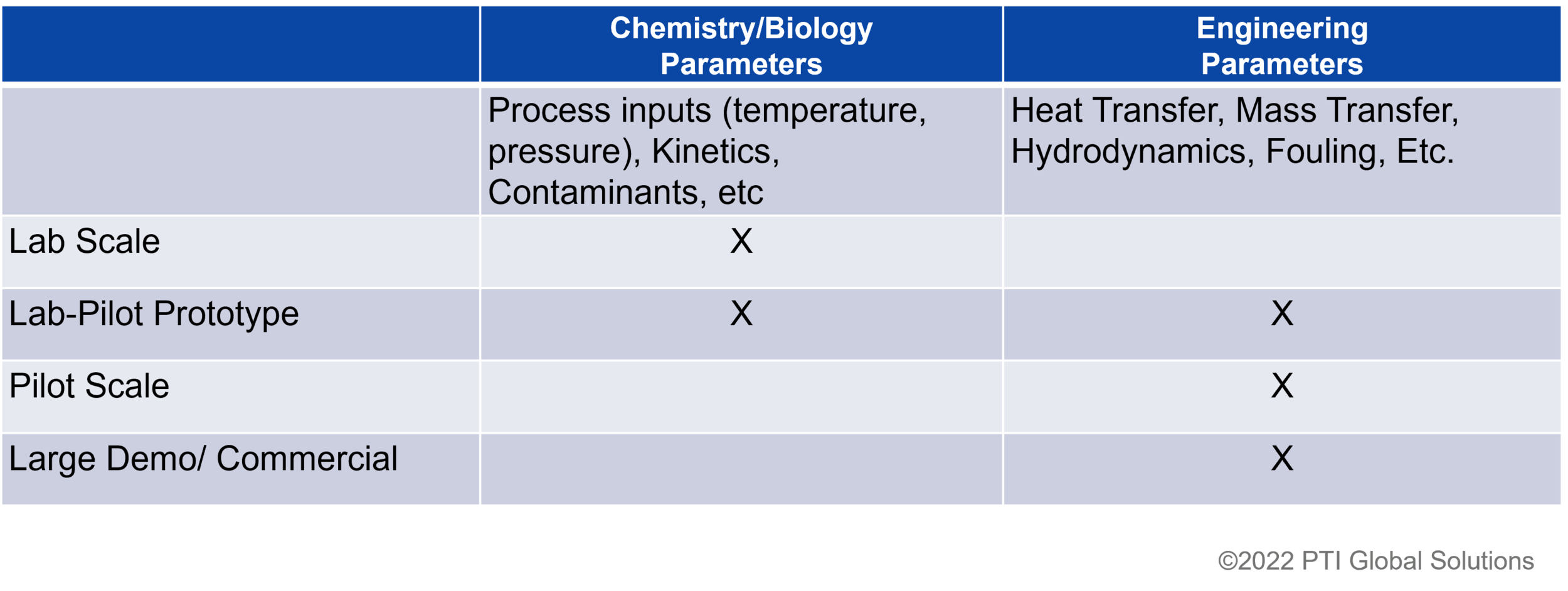

Typically, the scale-up timeline is the most critical of these. Often we must accept some risk to move quickly. The key is to understand risks, mitigate where possible, perhaps with some strategic overdesign and investing in R&D at all stages of scale-up.

To effectively move quickly while managing risk, we need creative engineering, effective experimental programs with critical data gathering at each stage, and useful modeling efforts.

Sebastian Klemm: How can you concretely support companies through scale-up challenges of new products & process technologies?

Michael Schultz: I help companies navigate the bumpy road of scale-up, providing process development services to validate key technical concepts, optimize the right parameters, and derisk the technology.

I am currently working with a company producing a novel polymer additive as they look to scale-up their technology. Having proven product manufacture at the lab scale, I am working with them to define and build their process technology at larger scales.

I also help clients better assess and understand their technology, by providing an internal engineering review of their technology, and guiding the team in a scale-up risk assessment.

I also enjoy working with clients to build capability. Going beyond producing deliverables, I view a project as a success, if I can transfer my knowledge and learnings so that I am finally no longer needed!

Click to visit the PTI Global Solutions website

Sebastian Klemm: How do you think the Inflation Reduction Act just passed in the U.S. can help turn the tide in favor of investing in sustainable technologies and clean energy solutions?

Michael Schultz: The Inflation Reduction Act[1] provides a number of financial mechanisms to stimulate further adoption of clean energy and sustainable technology in the United States.

The IRA is a predominately technology neutral approach, providing incentives across sectors such as power (wind, solar, nuclear), electric vehicles, transportation fuels, clean hydrogen, buildings and households. The IRA also provides much greater incentives for US manufactured content and prevailing wage requirements, providing a mechanism for US based manufacturing jobs to support this growth in clean energy.

Sebastian Klemm: Could you elaborate on how the scale-up of sustainable technologies interfaces with financial instruments?

Michael Schultz: The most successful sustainable technology scale-up efforts rely on many financial instruments to support scale-up and commercialization.

This can include grants from various public and private sources, joint development partnerships, venture capital funding, and for larger, first of its kind demonstration or commercial projects, specialized loan programs to support project capital investment.

In the past, I have provided technical due diligence support for various organizations making financial transactions in sustainable technology. This has included the US Department of Energy – reviewing applications for funding to support pilot and demonstration projects for the production of next generation biofuels, the US National Science Foundation – evaluating applications for early stage projects for sustainable chemicals, and a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) who was pursuing an acquisition of a commercial, or nearly commercial stage company in the sustainable technology space.

I am currently working with an early stage company with a novel technology for producing petrochemical alternatives from renewable feedstocks. I am helping them develop a process design for a pilot plant, and using this as a basis to estimate a preliminary, order of magnitude capital cost. This cost estimate will enable my client to plan and evaluate options to determine the best approach for financing for this project.

For each of these assignments it has been critical for me to assess the state of the technology in question, review technical and financial projections, and provide an assessment of any technical risk that should be taken under consideration.

Sebastian Klemm: You just recently completed a book chapter themed “Process Scale-up for Bioproducts: Enabling the Emerging Circular Economy”. Which particularities and crunch points do you address?

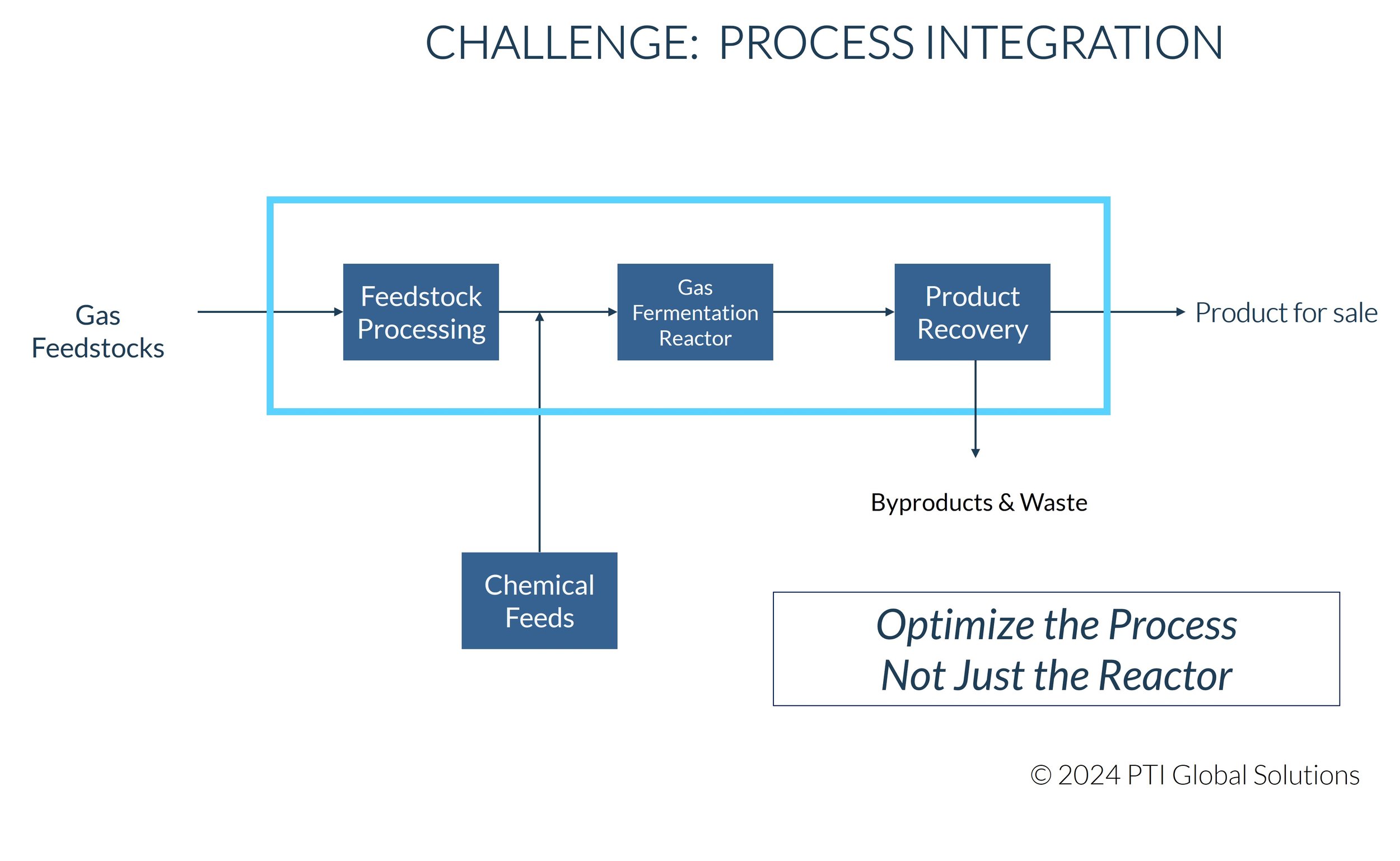

Michael Schultz: This chapter addresses the emergence of fuel, chemical, and food products produced from biobased feedstocks, using biobased catalysis and a combination of both of these elements. Similarities and differences in the scale-up of bioproducts compared to the scale-up of more conventional thermochemical processes using petroleum-based feedstocks will be presented, along with a case study and commercial success stories for the scale-up of bioproducts.

We see opportunities to contribute to a circular economy by producing products from renewable feedstocks and waste carbon. Challenges associated with the scale-up of bioproducts include:

However, with recent success stories such as the growth in drop-in, bio-based transportation fuels such as Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) and renewable diesel, new bioproducts such as polylactic acid (PLA) and bio-based replacements of conventional petrochemicals such as 1,4 butanediol and 1,3 propanediol (precursors to many polymers and other materials we use every day), the future is bright for continued growth in bioproducts.

For instance, the European Bioplastics Organization estimates that the global production of bioplastics will increase from 2.4 million tons in 2021 to 7.5 million tons by 2026.[2] Production of bio-based transportation fuels[3] such as biodiesel, renewable diesel, ethanol, and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)[4] is expected to increase as well in the coming years.

Sign up to meet Dr. Michael Schultz on August 25 to discuss “Financial Instruments for Scale-up of Sustainable Technologies”

Contact Dr. Michael Schultz with your interest in Scale-up of Sustainable Technologies..

References

↑1https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inflation_Reduction_Act_of_2022↑

2https://www.european-bioplastics.org/global-bioplastics-production-will-more-than-triple-within-the-next-five-years/↑

3https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-biofuel-production-in-2019-and-forecast-to-2025↑

4https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/pages/SAF.aspx